1) From Undergraduate Thesis to Personal Alarm

Few years ago, I devoted my undergraduate dissertation to the cultural life of internet memes. Not as throwaway gags, but as living arguments; small, repeatable packets of meaning that replicate like cultural genes and puncture authority where formal speech is punished.

Back then, I argued that memes were among the safest and sharpest instruments available to ordinary people who wished to hold power to account. I loved their audacity and their humility: funny enough to circulate; serious enough to sting.

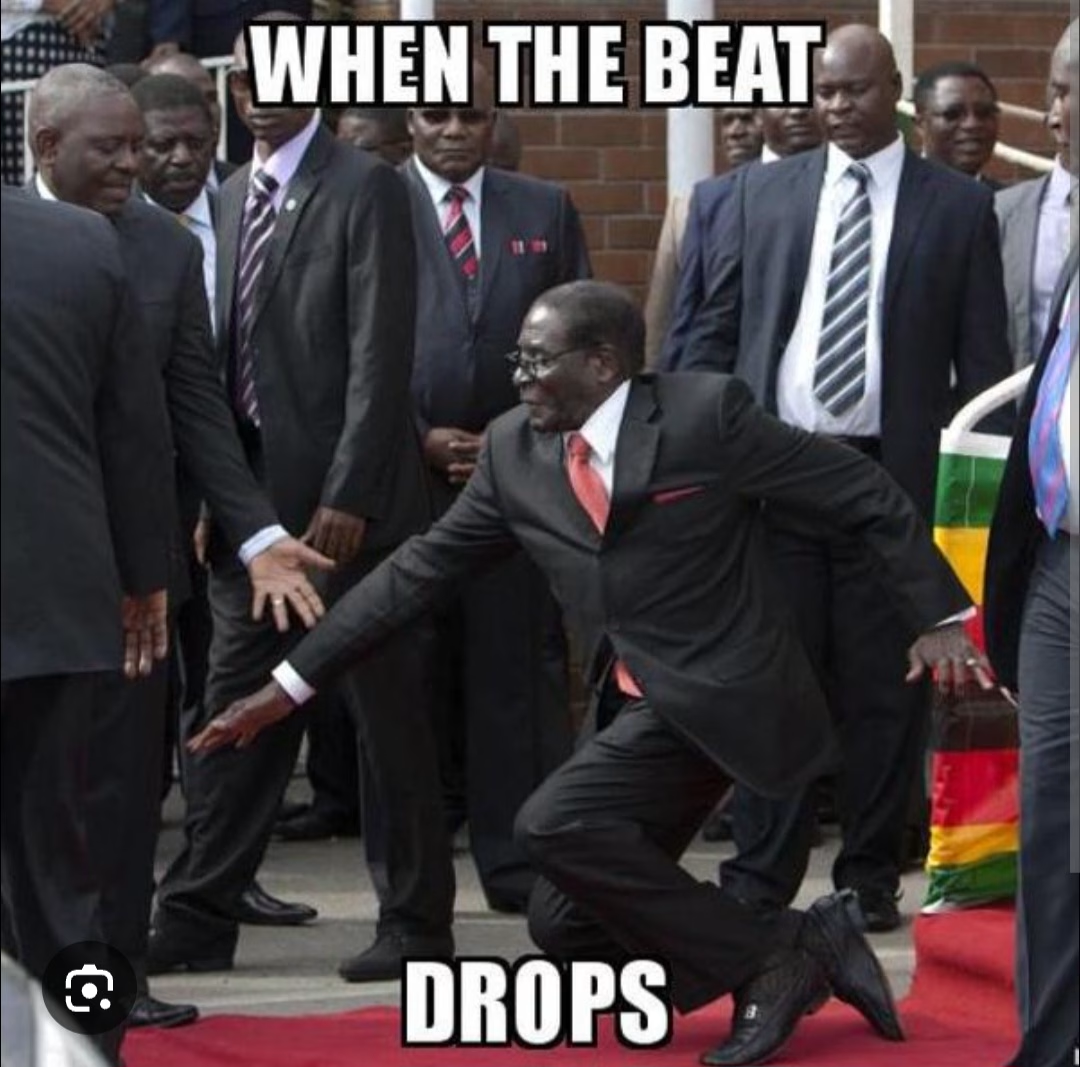

Today I write with a knot in my chest. In Zimbabwe, political memes; the kind that once turned everyday frustration into nimble satire—have thinned to a whisper.

The spirited irreverence that animated our timelines in late-Mugabe years has dulled under Emmerson Mnangagwa’s era.

Even visible creators on the social scene—Larry Mafukidze, for instance—largely avoid political bite, opting for safer, apolitical humour.

Individual choices are understandable; the collective effect is sobering: a public square less brave, a discourse less exacting, a citizenry less able to laugh power in the face.

This is not merely cultural drift; it is a democratic wound. In the hands of the oppressed, memes once enacted parrhesia—the risky obligation to speak even when danger shadows speech (Papadimos & Murray, 2008).

When humour loses its edge, power swells unmocked. When memes retreat to harmless entertainment, rulers are left to their shenanigans without the corrective of ridicule.

This essay [ largely borrows from my bachelor of science honors degree in media and society studies thesis] a lament, an argument, and a plan: to explain what memes are (and why they matter), to trace how and why our political memes withered, and to propose practical, ethical steps for their revival.

2) Defining Memes: Genes, Viruses, and Cultural Transmission

Richard Dawkins (1976) coined “meme” as a unit of cultural transmission, an idea or practice that spreads by imitation. Buchel (2012), drawing on Blackmore (1994), distills this into three operational features: variation (stories are rarely told the same way twice), selection (some variants grip attention and are copied), and retention (the core idea remains recognisable). Dawkins paired these with fidelity, fecundity, and longevity—how clearly the idea persists, how rapidly it replicates, and how long it survives.

Shifman (2013) reframes digital memes through three attributes: (1) cultural information that scales from person to crowd; (2) reproduction via imitation; (3) diffusion through competition and selection. Scholars often invoke gene/virus analogies.

From epidemiology, ideas can transmit horizontally (within a generation) or vertically (across generations), making memes potent carriers of public meaning (Diaz, 2013).

Critics warn the virus metaphor can imply passive contagion. But political memes are not mindless infections: humans author them with agency, purpose, and ethics (Jenkins in Shifman, 2013).

Crucially, memes are media-oriented phenomena (Valentine, 2014): captioned images, short clips, remixed screenshots, and text formats designed for swift circulation across informal social networks (Shifman, 2014).

In repressive or semi-authoritarian settings, they are tools to speak truth to power (Miltner, 2018), exceeding mere comedy to become vernacular political communication.

3) Hegemony, Subaltern Humour, and the Carnivalesque

Power controls more than factories; it controls meaning. Marx and Engels (1976) noted that those who command the means of production tend also to command the means of mental production.

In Zimbabwe, state-aligned media continues to propagate narratives that normalise elite interests and mark dissent as deviant. Memes offer the subaltern a counter-hegemonic channel, a vernacular newswire that bypasses editorial chokepoints.

Where urgency is suppressed, hilarity becomes the vehicle. Obadare (2009) reads humour in non-democratic contexts as weaponised levity: a survival tactic that doubles as critique.

Hariman (2008) calls satire a temporary invasion of power: jokes, comedic songs, comic strips, cartoons, caricatures, photographs and video clips, parodic performances, and street theatre re-stage hierarchy as ridiculous. People seldom confront authority openly for fear of silencing; they route critique through satire, which evokes smiles and provokes critical thinking at once.

The carnivalesque moment (Members, 2001) illustrates how, for short and long intervals, discourse escapes control; laughter defeats status and “everyone is supposed to just laugh.” State rituals meant to glorify authority are hijacked and converted into theatres of ridicule. For a moment, the powerful and the powerless are both weak and susceptible—the very essence of carnival.

4) Internet Networks and the Amplification of Memes

The internet links citizens both to each other and to those in power (Stromer-Galley & Bryant, 2011). Its networked architecture intensifies political effects (Bimber, 2012):

- Peer legitimacy: a meme forwarded by a trusted contact trumps a formal editorial.

- Asymmetric speed: a single image outpaces a press conference.

- Ephemeral freedom: control lags circulation; windows open where speech can race ahead of gatekeepers.

In Zimbabwe, these affordances made memes an efficient vehicle for the subaltern voice particularly in the late-Mugabe era, when netizens appropriated memes to resist and subvert state excesses (Communicare, 2016).

Memes were timely, grotesque, and distributed horizontally across WhatsApp, Facebook, Telegram, and X, turning mundane frustrations—fuel queues, potholes, or corrupt spectacles—into shared commentary.

5) Anatomy and Functions of Political Memes

Three traits defined Zimbabwe’s political memes:

- Immediacy: Memes respond rapidly to events, turning transient frustrations into commentary.

- Grotesque realism: Exaggerated faces, distorted signs, and absurd juxtapositions make authority look fallible.

- Horizontal spread: Peer-to-peer networks amplify messages across communities.

According to Distin (2005), successful memes are both self-assertive (they have a life of their own) and integrative (they mesh with public discourse).

They become mnemonic anchors, preserving the memory of events like ZRP interactions after demonstrations.

Memes are thus informal accountability mechanisms, allowing citizens to witness, interpret, and critique state behaviour even when formal media coverage is weak or biased.

6) Decline under Mnangagwa: Fear, Co-option, and Fatigue

Several interlocking forces contributed to the decline of Zimbabwean political memes:

- Fear: Vague laws and selective enforcement promote self-censorship.

- Co-option: Political actors adapt meme grammars for partisan propaganda, hollowing authenticity.

- Digital fatigue: Economic hardship and social crises drain the cognitive and creative bandwidth needed for humor.

- Commercialisation: Meme creators pivot toward monetisable, apolitical content.

- Fragmentation: Diaspora divides, language differences, and platform silos reduce shared cultural frames.

This combination has produced a public sphere where mockery of power is rare, and state narratives dominate unchallenged. Humor’s political function is compromised, and informal oversight through memes is weakened.

7) Consequences of a Silent Meme Culture

Without satire, citizens lose:

- Popular reportage: Alternative frames for public events vanish.

- Witnessing power: Citizens have fewer avenues to record and interpret authority.

- Memory retention: Collective recollection of abuses fades.

- Soft restraint: Officials face less subtle pressure to moderate behaviour.

As satire diminishes, hegemonic control of meaning intensifies, leaving discourse narrower and citizens quieter.

8) Blueprint for Revival

Revival requires infrastructure, craft, ethics, and strategy:

Decentralised Creative Circles : Small, trust-based studios (3–7 members) for ideation, prototyping, and ethical review.

Culture-Rooted Templates : Shona/Ndebele idioms, familiar objects (ZUPCO signs, Econet scratch cards), and everyday scenarios improve recognition and retention.

Layered Satire : Use metaphor and subtle symbolism to critique power while protecting creators.

Diversified Formats : Micro-videos, GIFs, interactive templates, and story-first mobile formats increase fecundity and fidelity.

Meme Library and Archive : Ethically curated, reusable images stored for future circulation, with metadata on date, context, and spread.

Training : Workshops on editing, captioning, semiotics, legal literacy, and digital security.

Strategic Distribution : Leverage micro-influencers, optimize timing, and encourage remix participation for maximum reach.

Diaspora–Home Networks : Mirror archives, enable translation across Shona, Ndebele, and English, and buffer risk while sustaining local voice.

Ethical Constraints : Target systems and powerful actors, avoid vulnerable individuals, respect privacy, and encourage anonymous authorship where necessary. Satire must comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.

9) Reclaiming the Hijack

Authority stages itself through spectacles: rallies, launches, and PR events. Memes can hijack these spectacles, converting intended glory into critical, viral mockery.

Pre-designed adaptable frames allow creators to act quickly, sustaining fidelity, fecundity, and longevity, turning humor into civic leverage.

10) Humane Stakes and Conclusion

I do not write as a distant analyst. I write as a Zimbabwean who feels the ache of silence. Political memes once allowed us to breathe under the weight of authority, connect with each other, and translate anger into shareable wit.

When satire retreats, fear grows; the sense that nothing can change grows. Without humor’s corrective, shenanigans flourish in the dark.

Zimbabwe’s political memes are not dead—they are dormant. With culture-rooted templates, decentralized creative circles, ethical guardrails, and strategic distribution, a memetic commons can be restored.

Memes are small, yet repeated faithfully, they form a language capable of changing worlds. If satire is a temporary invasion of power, let us organise those invasions ethically and creatively.

Teeth can grow back. And when they do, they must bite—cleanly, cleverly, and with laughter that reminds us we are still awake, still aware, and still capable of holding power accountable.