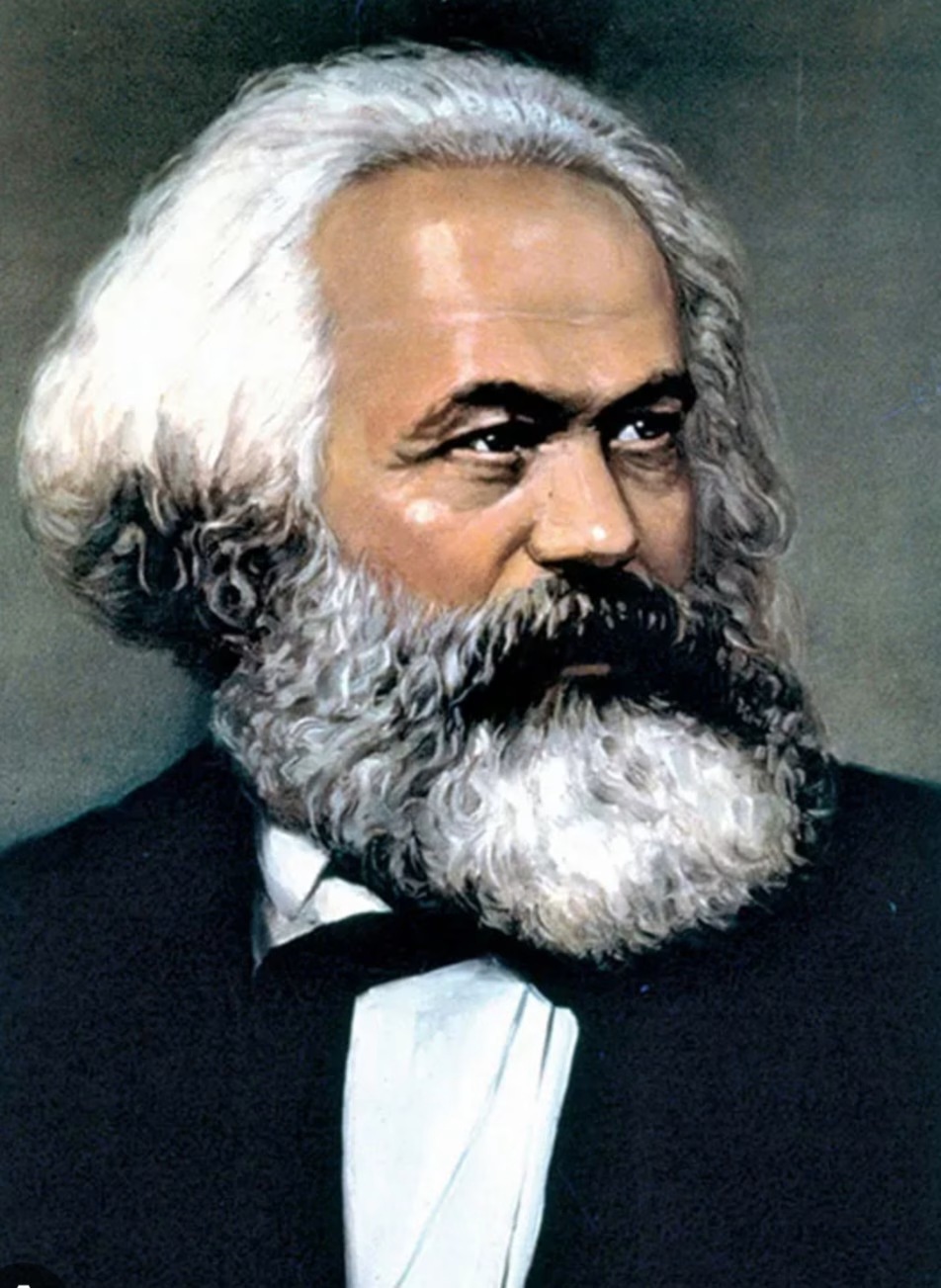

I was introduced to Karl Marx in my final year of high school. I still vividly remember the essay we were asked to write—centered on a quote from Marx: “Religion is the opium of the people.” I struggled to write the essay, but I fell in love with Marx the person right away.

As a communication student, I was exposed to more of Marx’s theories and philosophies, and the honeymoon continued.

Marx became a prophet to me—a citadel of past, present, and future phenomena. I became his disciple.

Unfortunately, one of his prophecies is yet to come to pass: the uprising that Karl Marx predicted has not yet arrived.

This delay has led me, Marx’s self-proclaimed disciple, to pen this reflection—an attempt to elucidate and offer hope to the congregation of the uprising, which has merely been delayed, not denied.

This epistle will take a closer look at the politics of nonviolent action and contrast it with the final revolution predicted by Marx.

“Philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.” — Karl Marx

In his vision of history, Karl Marx imagined a moment of rupture: a final revolutionary wave where the oppressed, the workers, the peasants, the poor—would rise, seize the means of production, and remake the world in their image.

Class struggle was not only inevitable; it was the engine of historical progress.

But more than a century later, despite widening inequality, rampant global exploitation, and an elite class richer and more insulated than ever, that revolution has not come.

The world Marx hoped would be torn from its roots has been met instead by a softer resistance: the politics of nonviolent action.

The question now is no longer whether the people will rise, but whether nonviolence has quietly replaced revolution—and in doing so, blunted its transformative edge.

A Global Chorus of Protest—Muted

From Wall Street to Nairobi, Cairo to Santiago, nonviolent protests have surged. Hashtags go viral, streets fill, placards rise, cameras roll and still, the systems stay intact.

Take Occupy Wall Street (2011): a decentralised movement that captured the global imagination with its critique of the “1%”.

Yet despite its scale, the financial system did not flinch. No banking executives were jailed. Inequality continued to soar.

Or #EndSARS in Nigeria (2020): an uprising against police brutality that united millions across class and ethnic lines. The protests were disciplined, decentralised, and stunningly nonviolent.

But when the state opened fire at Lekki Toll Gate, killing unarmed demonstrators, the system did not fall—it doubled down. A year later, the same corrupt structures remain.

Even Black Lives Matter, the largest civil rights movement in U.S. history, faced similar limits. For all its scale, slogans, and symbolism, policing budgets have largely increased, not decreased. Racism has not ended; it has adapted.

What unites these movements is not just their moral clarity—it is their limited disruption. They challenge power’s conscience, but not its wallet.

Nonviolence: The Velvet Cage?

Nonviolence is often framed as the ethical alternative to violent uprising. And indeed, its record includes some of the most morally admirable campaigns in history:

- Gandhi’s Salt March (1930),

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s March on Washington (1963),

- The Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace (2003),

- Tunisia’s Jasmine Revolution (2010-11).

Each of these movements disrupted economic or political systems at scale. But crucially, they worked not because they were peaceful, but because they threatened power with organized disruption, international scrutiny, and unsustainable costs.

That strategic core—pressure—is missing in many modern movements.

In his sharp critique, political theorist Mark Engler writes:

“Nonviolence works not because it is inherently virtuous, but because it can paralyze the functioning of power.”

Peace, in itself, is not resistance. Peace that lacks teeth is merely tolerable protest—a ritual of polite dissent.

Africa’s Revolutionary Traditions: Peace and Fire

Africa has never been a stranger to uprising, nor to strategic nonviolence. But it has also learned that peaceful protest is no guarantee of change when the state—or the global system—feels no real cost.

Liberia

In 2003, the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace, led by Leymah Gbowee, staged sex strikes, silent vigils, and mass sit-ins that cornered both rebels and government leaders into peace talks. Their methods were nonviolent—but profoundly disruptive, leveraging global attention and local cultural pressure.

Sudan

The 2019 Sudanese Revolution unseated long-time dictator Omar al-Bashir. It was driven by sit-ins, mass civil disobedience, and occupation of public squares—until the regime began massacring protestors.

Still, it remains one of the continent’s clearest cases of successful nonviolent uprising, achieved not by appealing to elite morality, but by breaking the regime’s control of the streets and narrative.

South Africa

The anti-apartheid struggle exemplified a hybrid strategy: mass nonviolent protest (Sharpeville, Soweto), international sanctions, cultural boycotts—and, yes, armed resistance via Umkhonto we Sizwe.

Apartheid did not fall because of pacifism—it fell because it became unprofitable and politically toxic to sustain.

The takeaway is clear: Nonviolence without pressure is performance. It must hurt the system to change it.

Where Are the Poor in All This?

In Marx’s imagination, the poor were the heartbeat of revolution—the ones with nothing to lose but their chains.

Today, their chains have become invisible: debt, hunger, gig work, surveillance, algorithmic policing.

The poor still protest—often more bravely and more frequently than anyone else:

- In Kenya, youth recently rose up against the 2024 Finance Bill, mobilising digitally and physically, forcing the Ruto administration to retreat.

- In Chile, students sparked protests in 2019 that ballooned into a nationwide revolt against inequality, forcing constitutional reform.

- In India, farmers occupied highways for over a year, resisting corporate capture of agriculture. Their protest was nonviolent—and sustained. It won.

Yet, the poor are still excluded from power, even in protest movements supposedly fighting for them.

The professionalisation of activism, the NGO-ization of revolution, and the rise of “activist celebrities” have often sidelined those who face the sharpest edges of injustice.

As Kenyan writer Nanjala Nyabola put it:

Has the System Outsmarted Protest?

Today’s capitalism is slippery. It does not just withstand critique—it sells it.

Movements are branded. Rage becomes content. Che Guevara ends up on tote bags.

The global order has become adept at absorbing dissent: it gives platforms, recognition, even funding—so long as nothing fundamentally changes.

And so protest becomes performance. Marches become festivals. Resistance becomes ritual.

All while billionaires double their wealth and the planet burns.

So, What Now? Is Violence the Answer?

No. Violence alone does not guarantee liberation. It often invites repression, instability, or simply transfers power from one elite to another.

History is full of revolutions that birthed new tyrannies: the Bolsheviks, the Jacobins, even post-colonial dictatorships.

But disruption is non-negotiable.

Whether through strikes, blockades, occupations, or economic sabotage, protest must make oppression unsustainable.

And here, strategy—not violence—is what matters most.

As Gene Sharp, the scholar of nonviolent resistance, argued:

“Power is not monolithic. It depends on the obedience of people. If enough people withdraw that obedience, the system fails.”

A New Proletariat? A New Revolution?

Marx’s “proletariat” is no longer the factory worker—it is the gig driver in Lagos, the garment worker in Dhaka, the Amazon packer in Alabama, the freelance coder in Nairobi.

This class is connected, precarious, and global. It may not carry torches, but it holds smartphones. It organizes in WhatsApp groups. It coordinates strikes on Telegram.

And when it finds solidarity across borders—when it organizes with purpose, not just protest for visibility—then Marx’s prediction might not be dead. Just delayed.

Power Concedes Nothing Without Disruption

To ask whether nonviolence works is to ask the wrong question.

The real question is: Does this protest cost the system anything?

If not, then it is a parade—not a revolution.

The poor do not need pity, permission, or more performance. They need power. And that power will not come from hashtags or symbolic marches alone.

It will come from withdrawing consent, refusing cooperation, and building alternatives—and, yes, sometimes, through confrontation.

Until that happens, Marx’s revolution will remain postponed—not by the failure of the poor, but by the pacification of protest.